[rt_reading_time postfix="min read" postfix_singular="min read"]

Gentlemen of the Gridiron

This article originally appeared on Front Porch Football on April 28, 2020.

On November 16, 2013, the Auburn Tigers hosted the Georgia Bulldogs for what turned out to be one of the most thrilling installments in the history of the Deep South’s Oldest Rivalry. After a furious comeback by the Bulldogs, Auburn faced a fourth down on their own side of the field, trailing with just a few seconds left. The play that followed will be remembered and discussed for decades to come in bars, BBQ restaurants, churches, and family reunions throughout the states of Alabama and Georgia. That night, the nation was enthralled by “The Prayer in Jordan-Hare.” An improbable, tipped-up-in-the-air, Hail Mary that propelled Auburn one step closer to what wound up being an SEC Championship season. Legends and heroes were born that night on the plains of eastern Alabama.

Just hours earlier, and 650 miles north on Interstate 85, the game between Hampden-Sydney and Randolph-Macon had also turned into a nail-biter. The Tigers of Hampden-Sydney found a way to stuff Randolph-Macon at the goal-line late in the fourth quarter, holding on for a two-point win. As the nation followed the Auburn-Georgia (and the Stanford-Southern Cal game out west), nobody was talking about Hampden-Sydney and Randolph-Macon clashing over their claim for a little corner of southeastern Virginia. Why would they? It’s just another game, right?

Not even close.

“The Game”

This was no ordinary game. It was The Game. A game – a rivalry – that has stood the test of time. A rivalry that began in the late 1800s and has survived two world wars and 22 presidents. “The Game typically draws 12,000-15,000 fans,” Connor Rund told me. Rund is a Hampden-Sydney alumnus and is currently the school’s Associate Dean of Admissions. Fifteen thousand fans may not sound like a lot to a Florida or LSU fan, but when you consider that both Hampden-Sydney and Randolph-Macon each have just over 1,000 students enrolled, that number is downright impressive. The two colleges started playing in 1893, the same year as the Iron Bowl. Both are historical institutions. Randolph-Macon was founded in 1830 by a pair of Methodists. Hampden-Sydney was established in 1775, prior to the Declaration of Independence and the formation of the United States. The two campuses are separated by about 80 miles. Both play in the Old Dominion Athletic Conference (ODAC). Tip O’Neill once said “all politics is local.” Well for the ODAC, “all football is local” with seven of the eight members located within Virginia. (The lone non-Virginian college is Guilford College in nearby Greensboro, North Carolina.)

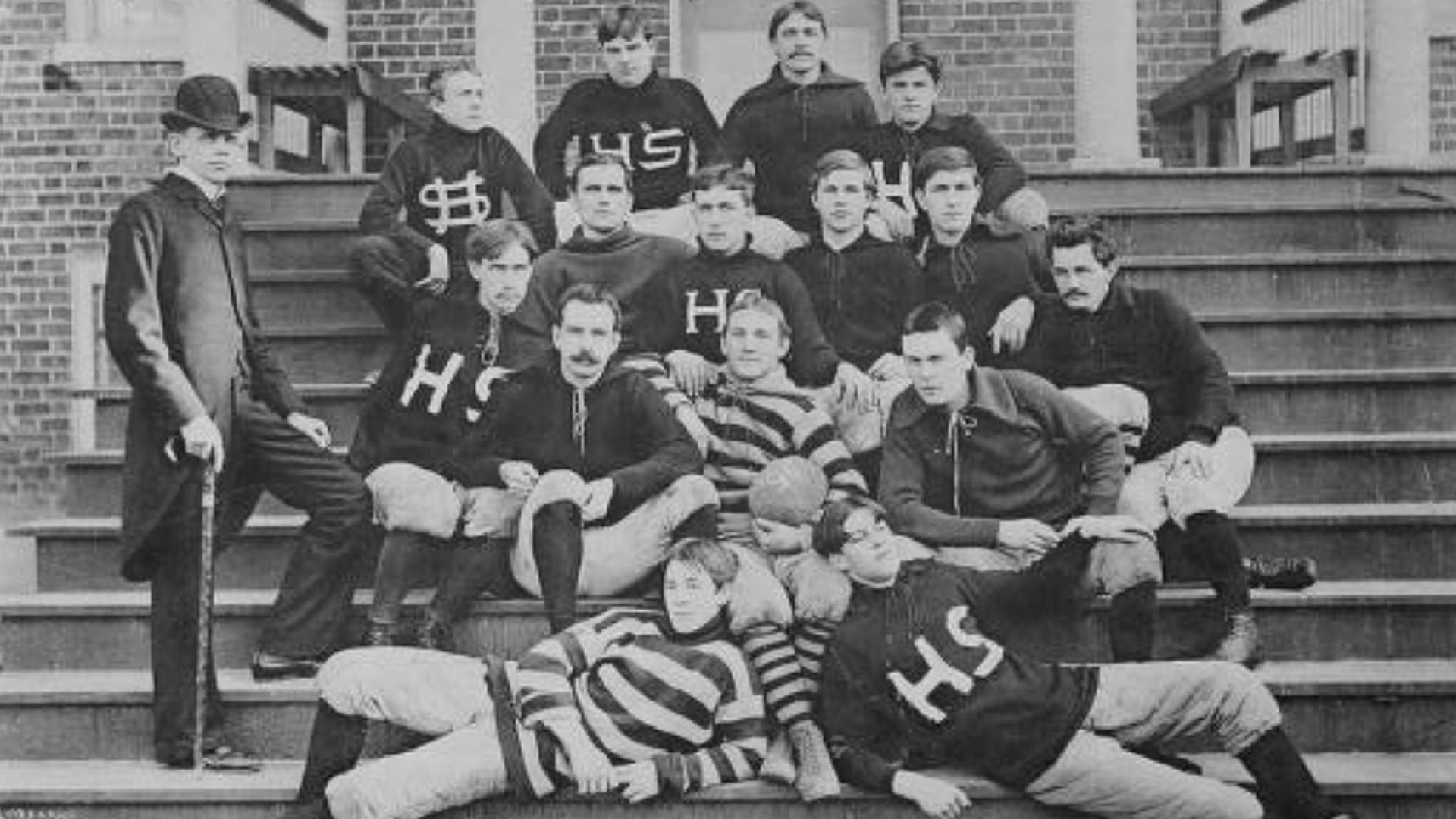

I decided to explore this historic rivalry from the perspective of Hampden-Sydney. Early in my college search, I thought about attending Hampden-Sydney. It had a great reputation in my high school, and a few older football teammates of mine went to Hampden-Sydney. One of them was Andrew Cooney, who was a defensive lineman for the Tigers and who now works for Morgan Stanley. “I wanted to attend a smaller school and to be a part of a winning culture,” Cooney told me. As the recruiting process continued, Cooney said it was pretty clear he wanted to go to Hampden-Sydney. “I loved the tradition. Hampden-Sydney has fielded teams since the late 1800s, so it’s pretty cool to be a part of something that has gone on for that long,” Cooney said.

“It’s an all-guys school in the middle of Virginia. Not exactly your typical college experience.”

Tradition permeates the campus, something that was not lost on Rund. “Hampden-Sydney is a truly distinct college experience,” he said. Cooney echoed that point. “It’s an all-guys school in the middle of Virginia. Not exactly your typical college experience.” In talking with both Rund and Cooney, it was clear that both loved the camaraderie and friendship that is championed at Hampden-Sydney. “I talk to my classmates every day,” Cooney said.

Football at a men’s college is, not surprisingly, wildly popular. “Hampden-Sydney’s entire fall is scheduled around the football season,” Cooney told me. Rund ran me through what a typical football game day looked like. It sounded a lot like a Saturday in Athens or Oxford or any other SEC town. “Staples of game days include elaborate tailgates, visiting ladies in sundresses, and students in either polos or coat-and-tie,” Rund said. “The campus truly comes alive on game day.” Part of the reason football Saturdays are so vibrant at Hampden-Sydney is because many alumni come back for games. Alumni from all generations gather in the Founder’s Lot. “Game days are unique at Hampden-Sydney because the tailgating continues throughout the game,” Rund said. To many SEC fans, this point may seem strange. When you go to an SEC game, you are either tailgating or watching the game, but never both. Not so at Hampden-Sydney. “The Founder’s Lot offers a great vantage point of the field so most alumni never end up leaving their tailgate.” After the game, students, fans, and alumni migrate to the fraternity circle for more partying and celebrating. “Post-game there is usually an oyster roast or a pig pickin’,” Rund told me. “Things may start up at 9 AM for an afternoon kickoff, and then after the game there are bands and parties happening all around,” Cooney said.

Bitter Rivals

It is important, however, not to confuse the pre-game and post-game parties for disinterest in what happens during the game, especially when Randolph-Macon is on the opposing sideline. “It’s one of the oldest rivalries in the country,” Cooney told me. He’s not wrong. According to many close to the programs, “The Game” is the oldest small-school rivalry in the South. Like so many other great Southern football rivalries, Hampden-Sydney and Randolph-Macon play their game during the final weekend of the regular season. And it doesn’t matter how either team’s season has gone up until that point. In an interview with Chris Preston featured on ESPN years ago, Hampden-Sydney football coach Marty Favret said, “going 1-9 is a good year if you beat Macon.” Many Hampden-Sydney alumni join Coach Favret in that sentiment. “We have a rivalry with Washington & Lee, but they prove to be a more cordial adversary,” Rund told me. “Randolph-Macon is certainly the biggest rival.”

And those aforementioned post-game parties can sometimes be cancelled depending on the outcome of The Game. In 1998, a brawl broke out between the two student bodies after a high-scoring game that ended with a narrow Randolph-Macon victory; afterward, visiting Randolph-Macon students tried to tear down Hampden-Sydney’s goalposts in celebration. That doesn’t fly in the South, especially between two bitter rivals. In 2003, there was a scuffle amongst the players before the game, this time on Randolph-Macon’s home field. “They thought we were jumping on their logo,” Coach Favret told Preston, “and our third-string offensive lineman [was ejected]. We ended up winning and he got the game ball.” While the bad blood rarely manifests itself in physical altercations, and both schools foster and cultivate good sportsmanship with their students, the rivalry is raw and energetic to this day. I asked Cooney what his favorite memory was of playing football at Hampden-Sydney. “Beating Randolph-Macon to win the ODAC Championship in 2013.”

“The Game” piqued my interest when it made a run in the Front Porch Football Instagram bracket we had set up to determine what Southern football rivalry was supreme. (Unsurprisingly, the Iron Bowl was crowned champion.) But after doing some research following the advice of Rund, I learned that Hampden-Sydney had more significant connections to the SEC than simply having a heated rivalry similar to the Iron Bowl or Egg Bowl. One of the more remarkable ties is Alexander Lee Bondurant, a Hampden-Sydney graduate and Latin professor at the University of Mississippi in the late-1800s. Bondurant designated red and blue as the Ole Miss colors and founded and coached the first Ole Miss football team in 1893. A couple of decades later. Dr. George Denny became the president of the University of Alabama. Denny was a Hampden-Sydney alumnus like Bondurant and had a similar passion for football. Denny also understood the importance of football in the South earlier than most college presidents. He knew that a winning football program would not only energize the students and alumni, but also would help spread the name of the university. Denny was (and still is) so beloved by the University of Alabama that his name, alongside Bear Bryant’s, is the namesake for Alabama’s football stadium.

In talking to Rund, I saw Hampden-Sydney alumni throughout the SEC. One of Georgia’s most renowned presidents was Moses Waddel, a Hampden-Sydney graduate that, according to a historical marker next to the Arch, oversaw a period of tremendous growth for the university. The first chancellor of Vanderbilt University, Landon Garland, was also a Hampden-Sydney alum.

Land of Leaders

Ultimately, it should come as no surprise that Hampden-Sydney alumni have held such prominent roles in leadership. “You’re developed as a leader at Hampden-Sydney,” Rund told me. Hampden-Sydney isn’t unique in that it develops productive graduates. But it is exceptional. More than most colleges, Hampden-Sydney places a premium on gentlemanliness, industry, honor, and leadership. Those traits may be most visible in the business world and in the community, but they were born in the classroom and on the football field.